Uncovering Callanish’s Secrets: An Archaeological Tour

Update: With great sadness, I’m reporting that Callanish researcher and archaeo-astronomer Margaret Curtis died in March 2022. Read on for the insights Margaret shared with me when I visited the Callanish Neolithic sites on the Isle of Lewis in 2012.

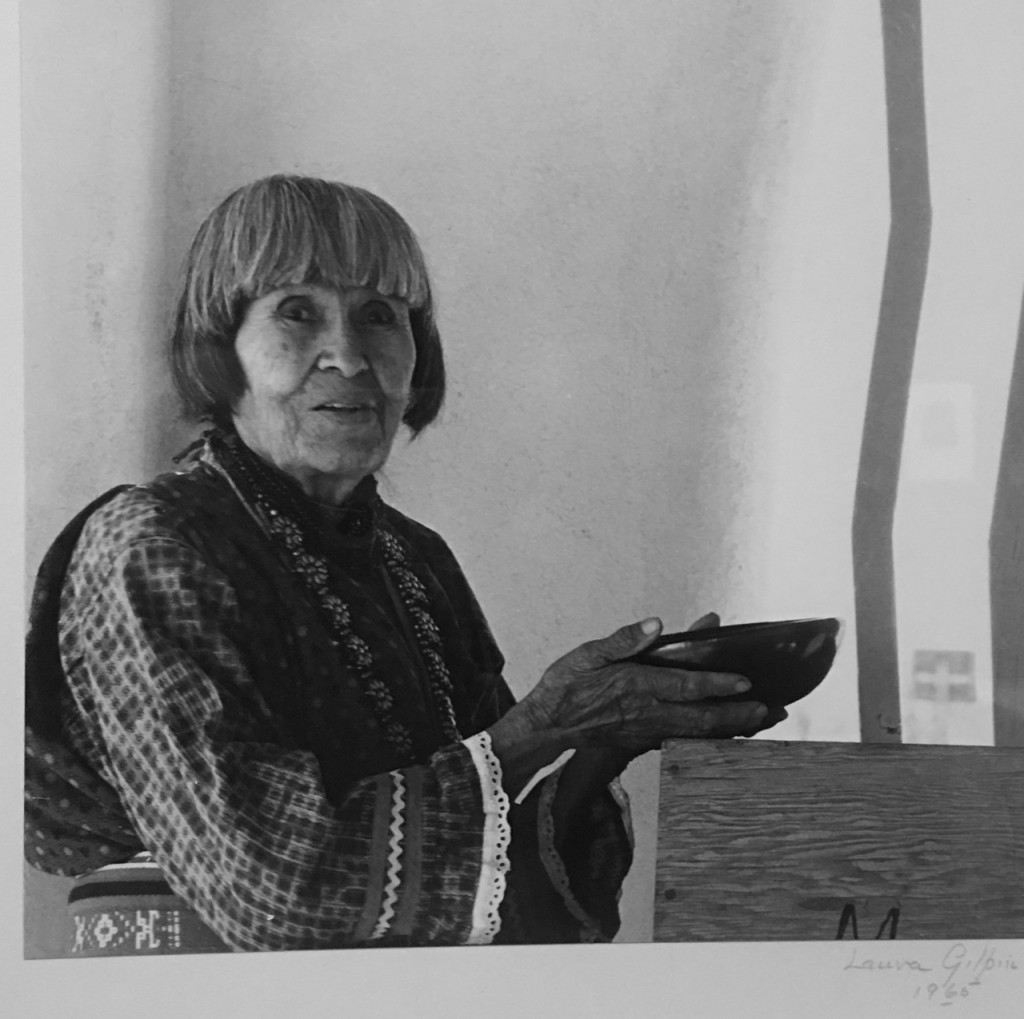

Seeing, touching and photographing the astonishing Callanish stone circle on Scotland’s Isle of Lewis is only part of the delight of visiting. Because I’m more than a little obsessed with these prehistoric treasures, I wanted to learn what archaeologists think about this particular circle when I visited. So I did a little research and dug up a wonderful guide, Margaret Curtis, who has observed and excavated sites around Callanish for almost 40 years.

Margaret Curtis led tours of the Callanish standing stones. Here, in 2012, she explained the Triple Goddess stones inside Callanish III circle. © Laurel Kallenbach

I first read about archaeo-astronomer Margaret Curtis on artist Jane Tomlinson’s blog post, and knew that I had to meet Margaret. So I phoned her before I left the States to request a tour. Just like that, I had an appointment with a local expert!

As it turned out, Donald and Nita Macleod, the owners of Leumadair B&B where I stayed, are good friends and supporters of Margaret’s research. So, Donald drove me and Margaret on not one, but two, tours of Callanish—which encompasses far more than just the large circle I’d journeyed to see. [Note: The Macleods have retired, and Leumadair B&B is now closed.]

Many megalithic sites—including other circles, stone rows, burial cairns, and single standing stones—dot the countryside and farmland. Collectively, these 20-plus sites are called the Callanish Complex.

Monoliths, Moons, Mountains, and Myths

I was so lucky to hire Margaret Curtis to be my guide. She shared her enduring passion for the secrets and mysteries of the extraordinary Callanish Complex.

Here’s Margaret Curtis with the Callanish I endstone in 2012. This stone marks the end of the avenue of standing stones that leads up to the central circle. © Laurel Kallenbach

Over the decades, Margaret’s life’s work included logging untold hours examining the stones; finding ones covered by thousands of years of peat; and unearthing hidden, but important, sites.

Yet earthworks and rocks are just part of the story. Like the Callanish builders four to five millennia ago, Margaret was also a student of the sky. Although she never formally trained as an archaeologist or astronomer, she chronicled how ancient people carefully planned the Callanish sites to mark a number of astronomical events, including a lunar rise and set that occurs only every 18.5 years. Now that takes decades of observation on both the part of the builders and the archaeological sleuths! (Over the years, Margaret carried out her extraordinary work and research with her first husband, Gerald Ponting, and with her late husband, surveyor Ron Curtis.)

The standing stones on this Scottish island align with the sun and moon, yet there’s a third element at work here that makes the Callanish Complex extremely brilliant and, well, complex. On the horizon to the south are mountains, dominated by Mt. Clisham. If you use some imagination, you can see the head, breasts, belly, and knees of a reclining form. In English, she’s called Sleeping Beauty, but in the old Gaelic she’s “Cailleach na Mointeach,” the Old Woman of the Moors. I like that name so much better than the one referencing the fairy tale.

Behind the Callanish Visitor Centre is the reclining figure of the Old Woman of the Moors. The blue mound just to the left of the highest peak is her face. You can just make out the nose in the center of her “face.” © Laurel Kallenbach

The Man (or Woman) in the Moon

Cailleach na Mointeach, who also represents the Earth Mother or Earth Goddess, is the key to why all the Callanish standing-stone sites were built, archaeo-astronomers believe. The circles are all located in areas where viewers could see the once-every-18.5-year lunar event: when the full moon, at its rare southern extreme, rises from the sleeping body of the Old Woman of the Moors.

This celestial event was important enough that prehistoric people erected stones that would frame this special moonrise and moonset. As she wrote in Callanish: Stones, Moon, and Sacred Landscape (coauthored with Ron Curtis): “Seen from the Callanish area, the moon at its south extreme rises from some part of the Sleeping Beauty, passes low at due south, sets into the Clisham Hills, then reappears briefly and dramatically in the deep valley of Glen Langadale.”

Callanish III stone circle, where the two center stones frame the face of the Old Woman of the Moors. This is where the moon rises every 18.5 years. © Laurel Kallenbach

And there’s more: when the full moon reappears in the valley, a living person can stand inside the ring of stones and be silhouetted by the moon—a vision that’s as heart-stopping today as it must have been in 2200 BC. (You can see some photos of this at The Geo Group website. The last event occurred in 2006.)

Walking with the Wise Woman of Callanish

In 2012, when she was in her late 70s, Margaret was truly the Wise Old Woman of Callanish. She said she was personally most interested in the area from a scientific point of view, but she acknowledged that her work also drew from local history, folklore, and ethnology. She gave tours to modern pagans and goddess worshippers, and she said that their insights into earth-based rituals informed her work. After all, there are no written records about Callanish, so oral tradition in the form of legends can contain kernels of truth.

The white mineral deposits on the bottom half of this stone create the Horned God, found at Callanish I. His large torso is slightly leaning to his left, and you can make out what appear to be “antlers” on his small head. © Laurel Kallenbach

At the start of my tour, Margaret took me to her workshop, where she demonstrated how the Callanish stone circles were designed to be ellipses—not just a poorly made circle—and how the stones were erected. She even let me hold a 4,000-year-old arrowhead—a tiny remnant of the prehistoric people who lived on this island. Mind-boggling!

Later, we ambled through Callanish I, the main stone ellipsis, which Margaret called both “a stone-age computer” (because it marks solar and lunar events) and a “community center” (because it was a gathering place for singing, dancing, and burying the dead).

In a way, Callanish is still a community center—of World Heritage Site calibre. Over the days I was there, I heard visitors from several continents speaking various languages, and I watched children have foot-races down the stone-lined avenue, the ancient entryway to the main circle. I saw photographers and artists capturing images of the stones on paper or in digital format. Couples paused to kiss. Baa-ing sheep gazed over the fence at the stones. Dogs lifted their legs to pee on the stones. Ravens alighted on the monoliths. Many people sat amid the stones and meditated or wrote in their journals. Occasionally someone would sing.

“People tuck flowers or special, meaningful items into the stone gaps and graves here,” said Margaret. She pointed out that someone had climbed up and left a carved bone atop the tall End Stone of the Avenue—the very top that had been broken off since Victorian times and that Margaret found amid a pile of rocks. The top has now been cemented on, thanks to her!

If you look through the rectangular peephole formed by two separate stones, you may be able to see sunrise at Summer Solstice. ©Laurel Kallenbach

Along the way, Margaret related the individual history of many other stones, which she knows like the back of her hand. She pointed out a stone in which the hornblende crystals naturally form a shape that looks strikingly like the pagan Horned (or Antlered) God. The gneiss stones were surely chosen because of their shape, size, and the presence of quartz (a crystal associated with the sun) or hornblende (a mineral associated with the moon).

She also showed me the notches in two separate stones in the Callanish I circle. At Summer Solstice, these two notches form a square “viewfinder” through which you can see the midsummer sunrise. In addition, an east-west line of stones lets you sight through two stones to witness both the Spring and Fall Equinox.

Stones That Mark Celestial Events

There are really too many highlights from Margaret Curtis’ tours for me to relate, but here are a couple of other Callanish sites on the Isle of Lewis that are well worth visiting:

1. Barraglom Narrows stones (Callanish VIII)

These standing stones are picturesquely positioned on a cliff overlooking the narrows that separate the Isle of Lewis from the Isle of Bernera. By sighting the east horizon from the third large stone here, you can spot two standing stones on a distant ridge. On Beltaine (May Day) you can see the sun rise between the two standing stones.

The standing stones at the Barraglom Narrows are just part of about 20 prehistoric sites that comprise the Callanish Complex on Scotland’s Isle of Lewis. © Laurel Kallenbach

2. Callanish III Stone Circle

I loved visiting Callanish, especially at about 7:30 p.m., when this photo was taken. I’m wearing rain pants to cut the sharp wind and also to let me sit in the grass by the stone of my choice without getting damp. All is not paradise on this Hebridean island. Shortly after taking this picture (in early August), I had to put on my wool cap and gloves for warmth. And the midges started biting at sunset. Still, there’s no place I’d have rather been.

Sitting in what’s now a cow pasture (watch out for cow pies!), this small, elliptical circle surrounds four stones, which Margaret believes represent the Triple Goddess (one each for the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone) and her male consort (represented by a tall, penis-shaped stone).

If you stand at a sighting stone a few hundred yards outside the Callanish III circle, you will see the full moon rise at its rare southern extreme (every 18.5 years) from the body of the Wise Woman of the Moors—and that event is exactly framed between two stones.

Four hours later, if you move to a second sighting stone that’s at a different angle to the circle, you see the moon reappear from behind the mountain in the valley of Glen Langadale. This too, is perfectly framed by two stones in the circle.Well, if anyone is still reading this too-long post, you’re probably as much of a geek about ancient standing stones as I am.

Here’s to looking at the moon…

—Laurel Kallenbach, freelance writer and wannabe archaeo-astronomer

For more info, click on Visit Scotland or Visit Isle of Lewis.

Updated: April 2022

Related posts:

- 5 Reasons “Outlander” Fans Will Love Scotland’s Isle of Lewis

- The Magic of Scotland’s Callanish Standing Stones

- Farm B&B with a Callanish View

- Finding Inspiration on Scotland’s Isle of Cumbrae

- Full Circle: Standing Stones in Ireland

- An Irish Dolmen and a Magical Dog

- A Birthday among the Ancient Rocks of Stonehenge

- Exploring Myth and Prehistory at England’s Rollright Stones