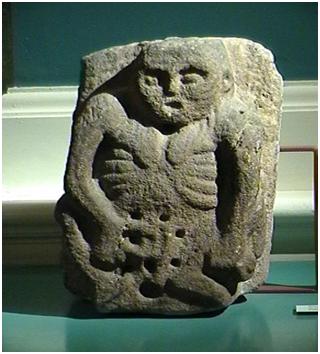

This sheela-na-gig from Seir Kieran in County Offaly was on display at the National Museum of Ireland when I visited in 2004.

Think Indiana Jones. Think of a quest for an archaeological treasure. Picture me, wide-eyed and somewhat crazed, tearing around Ireland’s rural backroads seeking a treasure. See me wading through thigh-high weeds still wet from the morning dew. Hear me cursing out loud to myself about driving on the left-hand side of the road.

Unlike Indiana Jones, no one was chasing me with a gun or a sword. I was not searching for the Holy Grail or the Crystal Skull or the Lost Ark. I was searching Ireland for sheela-na-gigs—peculiar, medieval-era stone carvings of haglike, naked women displaying their private parts.

If you read my last post, you know that during my 2004 Ireland trip, I had a bit of an obsession with searching out sheela-na-gigs, which are found on the walls of churches and castles in England, Wales, and Scotland, and Ireland. There are more known sheelas in Ireland than anywhere else, and on my journey through Éire, I stalked the gargoyle-like carvings literally over hill and dale.

Searching for Sheelas at the National Museum of Ireland

I started in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, which houses fabulous archeological treasures, such as the Indiana Jones–worthy Ardagh Chalice made by 12th-century monks of gold, silver, bronze, brass, and copper. And the golden, delicate Tara Brooch made in 700 AD is priceless.

Displayed alongside these magnificent works of Celtic art were two crudely carved sheela-na-gigs—much less flashy than the aforementioned treasures, but also much more intriguing. No one really knows why these “hags of the castle” were located like gargoyles on Anglo-Norman-era churches and medieval castles. But one thing we know for sure: they had meaning for people ten centuries ago.

“The name comes from the Irish language, although its meaning is uncertain,” says Dr. Eamonn Kelly of the National Museum, and author of Sheela-na-Gigs: Origins and Functions. “The most likely interpretations are Sighe na gCíoch, meaning “the old hag of the breasts,” or Síla-na Giob, meaning ‘sheela (a name for an old woman) on her hunkers.’”

I emailed the National Museum in advance and got permission on my visit to be escorted into the museum’s vaults to see a dozen more sheelas that weren’t on display but that have been in the museum’s care for decades—some for an entire century.

It’s an amazing thing to be face to face with works of sacred (or profane) art that I’ve only read about in books. (One of my favorites is The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland and Britain by Joanne McMahon and Jack Roberts because it includes a catalogue with drawings of sheelas.) So, after I got my fill of sheelas in the museum, I set off to search for others, in situ.

The Sheela-Na-Gig of Esker Castle

Locating the sheela-na-gig—reportedly located on the walls of a ruined castle near the tiny village of Doon, in County Offaly—was quite an adventure. I felt completely lost while trying to find the village, and once there, I had no way of knowing where Esker Castle was. (If there was a sign to it, I never saw it because I was too busy driving on unmarked roads.)

This sheela-na-gig was a cornerstone on Esker Castle, near Doon, Ireland. The sheela-na-gig’s right hand passes underneath her right thigh, and her left hand reaches over her left thigh to expose the vulva. Esker Castle, Doon: The sheela-na-gig her right hand passes underneath her right thigh, and her left hand reaches over her left thigh to expose the vulva. ©Laurel Kallenbach

Luckily, from the road, I could see a hilltop ruin of what might be a medieval castle—though I wasn’t positive. I pulled onto a gravel road and drove to what I hoped would be the ruin, but soon the road disappeared into grass and there wasn’t enough space to turn around. My car had pretty bad sightlines for backing up (or maybe I should have looked backwards over my left shoulder instead of my right!) but I managed to drive in reverse back to the “safe,” graveled road. At the foot of the hill with the castle, I parked on a gravelly pullover spot, pulled on my rain pants and rain jacket, laced up my sturdy hiking boots, and then set off as it began to drizzle.

Foolishly, I chose a steep trail that led up toward the castle—ancient fortresses were designed to be difficult to reach—but halfway up it became apparent that no pedestrian had used it in ages—perhaps since the Middle Ages. I picked my way through brambles and briars; thorns clawed at my hair and rain jacket. I lost my traction in the mud. At last, though, I emerged at the foot of the ancient stone walls, sweating and hoping that my grit and determination would be rewarded by an easy-to-find sheela-na-gig.

The luck of the Irish was with me, because I turned the corner, and there she was, halfway up on the wall of the castle amid twisty ivy vines to the left of the castle entrance. She was carved horizontally on a cornerstone, even though she’s depicted in a standing position, with both toes pointing to the right. A shiver of excitement passed through me. I’d done it: located a sheela-na-gig in a non-museum location!

The first thing I noticed was the sheela’s large, bald head, part of which was covered in white. (Maybe someone whitewashed her for ease of seeing her?) Her mouth was open as if she were grimacing or saying something. She was a bit eerie, this sheela-na-gig: otherworldly and ancient and none too inviting despite her naked breasts (just two little mounds) and spread legs.

I took some photos, but it was difficult to relax and reflect because a nasty wind had come up. Besides that, the castle ruins were gloomy, the weather threatening. I was already a bit traumatized from the ordeal of the disappearing road and the brambly path. All I could think was, What if my car gets stuck here or I fall down the hill and sprain an ankle? There was a farmhouse just 100 meters away, but I was spooked just the same.

I walked around a bit, shielding my camera inside my raincoat from the wind-driven rain. I wanted to see the sheela from several angles. And then, Irish luck struck again, and I discovered another path—a real one this time—that I might have discovered if I hadn’t been in such a frantic hurry at the beginning. Compared to the path up, this one was fairly tame. Soon I was inside my rental car and peeling off my wet jacket. As I drove off, I took one last look at the towering walls—the home of the Esker Castle sheela-na-gig—and bid a hasty farewell.

The Sheela-Na-Gig of St. Munna’s Church

Although Indiana Jones got lost a number of times on his adventures, I seemed to have more than the usual mishaps on the sheela route. Two days after I almost missed the Esker Castle sheela, I again got confused while searching for one of the stone carvings on a church in County Westmeath. First, I got lost in the nearby town of Mullingar. Shortly later, I took two more wrong turns around Crookedwood before I eventually happened upon St. Munna Church, which ironically looks more like a castle than a church because of its crenellated tower.

I parked and walked up to the 15th-century church with its old cemetery. The four-eyed sheela-na-gig was in plain sight over a broken-out trefoil window, and just a moment after I saw her, I was greeted enthusiastically by a wag-tailed black dog from a farm across the street.

This sheela was fairly eroded, but she either has four eyes or two holes drilled into her head above the eyes. Again part of her head was blotched with white—I think it must have been some sort of lichen. This sheela also had an open mouth, as if she were speaking, and this one looked like she had a beard. Though her hands were on her abdomen, there was little view of her genitals other than a deep hole. It was easy for me to imagine this sheela acting the role of a gargoyle—perhaps because her features we so indistinct. It’s possible she was defaced by people in more recent centuries who would have considered this stone carving obscene.

Perhaps it was because I was very tired, but I didn’t spend too much time with this sheela. And I felt a little out of place somehow, despite the adorable dog. This was the case a number of rural sites in Ireland. I disliked being among lots of tourists, but I also sometimes wished I wasn’t the only human around. So, I paid my respects to the naked, stone woman who has gazed fiercely down upon centuries of church-goers with her four eyes. Then I moved on to my next destination: the Loughcrew archaeological site, also called Slieve na Calliagh (“Mountain of the Hag”).

—Laurel Kallenbach, freelance writer and editor

Originally published March 2016

Read more about my travels in Ireland:

- Archways into the Irish Past (about sheela-na-gigs)

- Jedi Knights Arrive in Ireland

- An Irish Dolmen and a Magical Dog

- Full Circle: Standing Stones & Driving in Ireland

- Take a Celtic Seaweed Bath on Ireland’s Coast

- On Downings Beach

- Legendary Green Spa in Ireland

- Time Traveling to Ireland’s Temple House

- A Visit to Mythic Ireland

No matter what you’re passionate about, traveling the world to seek it out is a good thing. Female gargoyles, baseball, the perfect espresso: stuff worth searching the globe for!

Oh my gosh Laurel, this Sheela stuff is SO interesting… you have me in the palm of your hand.

A reminder of something…? The Sheela at St Munna church appears to be holding her chest open… exposing her heart and the sadness there within? And 4 eyes before glasses were invented. a way of seeing in as well as seeing out. And this one seems to have lost her femaleness and seems more male. Oh to uncover what the thinking was… Medieval scholars should be consulted. I’m going to order

Land of women. and in the mean time thank you for scrambling all over the place collecting this information. These things have deep feminine roots! And who were the carvers more likely to be? men. So what was their message… beware of a hag and her exposed vulva?

Maybe that’s it… trouble ahead. Like a stop sign. Just guessing.

Thanks, Jean! I’m so glad that you “get” my fascination with sheela-na-gigs. I like your interpretations, and you’re right: these things DO have deep feminine roots. That’s important from a time when women were invisible in history!

Like your blog.

When next in Ireland come visit me in West Cork.

I have a replica of a famous stolen Sheela.

I wrote the booklet Sheela na gig in 1991.

And I’m about to publish a more substantial book on the subject.

Best Agus Slán

Jim O’Connor

Thanks for the invitation, Jim! I’ll keep it in mind next time I’m traveling to Ireland!