IN WINTER, OREGON’S CENTRAL COAST IS A DRAMATIC PLACE TO WATCH WILDLIFE—ESPECIALLY PEAK MIGRATIONS OF GRAY WHALES AND WILD WEATHER.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I’m reminiscing about travel adventures of yesteryear. This trip was taken in early January of 2010.

Wind lashed the craggy Oregon shoreline, driving rain in horizontal sheets across my window. In the drab, January-morning light, it was impossible to tell where the steely sky met the pewter sea—yet somewhere out there were gray whales. But where?

A gray whale breaching. Photo Andre Estevez (Pexels)

The whales’ winter migration is the reason my husband and I came to Depoe Bay, Oregon’s whale-watching capital on the central coast. From mid-December to mid-January, the leviathans swim by—as many as 30 per hour—bound for Mexico’s warm waters. Though the whales also cruise these waters during spring and summer, winter is tops for sheer numbers. It also happens to be storm season.

Scanning the watery horizon from our oceanfront rental condo, Ken and I spied a posse of pelicans strafing the waves with their fish-seeking beaks, and sea lions, whose sleek backs flashed in the frothy waves. But no whales.

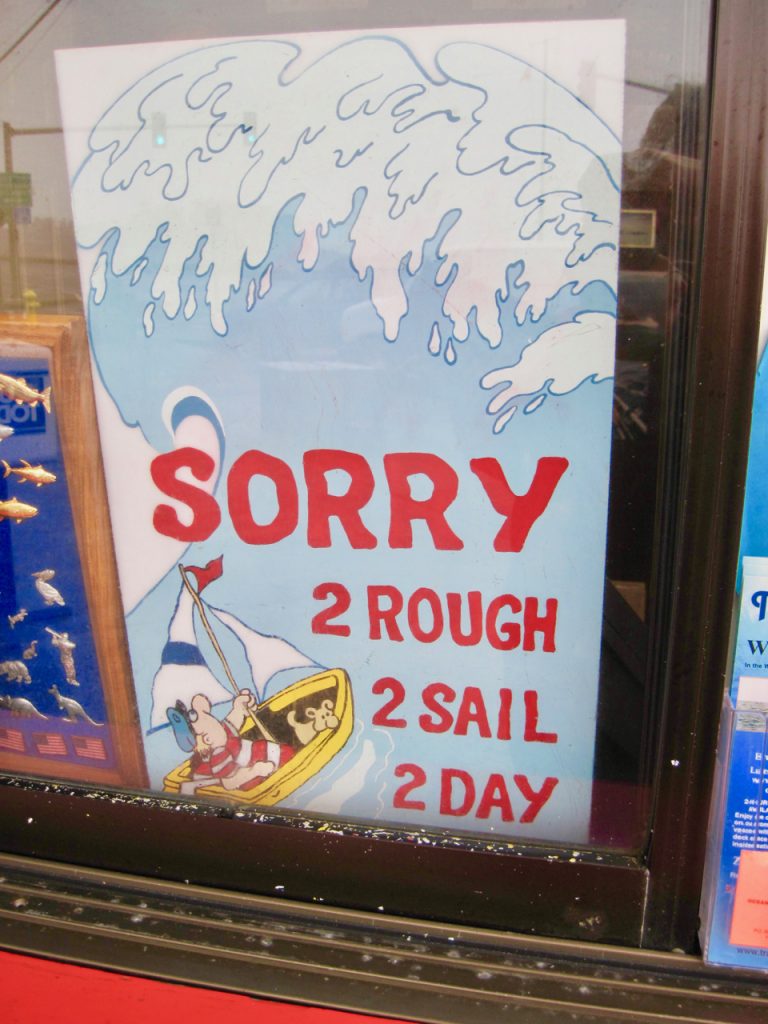

Sign of a blustery time ©Laurel Kallenbach

After breakfast, we donned raingear and began exploring. Depoe Bay, a charming fishing village 12 miles north of Newport on the Pacific Coast Scenic Byway (Highway 101), sits right on the water. A sea wall runs the length of the three-block downtown, where a geyser-like “spouting horn,” sprays water skyward when waves hit the lava tunnel. We ducked into a handful of gift shops and art galleries to escape the rain. Not surprisingly, the sign at one fishing/whaling charter read: “2 Rough 2 Sail 2 Day.”

Stormy Weather

With damp spirits, we visited the Whale Watching Center in Depot Bay, which is run by Oregon Parks and Recreation. The Center’s museum is packed with information about these marine mammals, which grow to the size of a school bus and eat 1 ton of mysids (tiny shrimp) daily. From the elevated indoor/outdoor viewing station, park rangers answer questions and point out blow spouts (caused when whales surface and exhale). Check in advance for opening times.

Whale Watch volunteer Cheri Bush wore a “Whale Spoken Here” button pinned to her vest. “Two days ago, we spotted 26 gray whales,” she reported. “You need good visibility, because in winter they stay 5 to 7 miles offshore. On a clear day you can see the blows without binoculars.”

Caught by cetacean fever, Ken and I decided to visit the best whale-watching overlooks along the Coastal Highway in hopes that the weather would clear. Of 26 overlook sites in Oregon, eight are clustered between Depoe Bay and Newport. During the annual Whale Week, volunteers stand ready from 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. to help you spot whales.

A volunteer at Depoe Bay Whale Watching Center scans the horizon for signs of migrating whales as they swim south. ©Laurel Kallenbach

We started at Boiler Bay Scenic Viewpoint, just north of Depoe Bay, where gusts pummeled us with a rain/salt-spray mixture. We peered from under our rain hoods to see a misty bay with a cave and waterfall. A rusted boiler from a 1910 wreck poked from the water, and three wet-suited surfers tested the waves. Under better conditions, this spot would be perfect for detecting whales, but besieged by weather, we soon headed south to the Rocky Creek overlook where we admired the foggy ocean from the car.

Next stop: the ominous-sounding Cape Foulweather. Captain James Cook named this panoramic promontory in 1778—and it certainly lived up to its name that day. Yet, as we beheld miles of coastline, it was easy to imagine whales cavorting offshore. What’s a little rain to them?

A mile down the road was Devil’s Punchbowl, a popular whale- and storm-watching overlook where the ocean slams into a hollowed-out rock bowl. We quickly moved on, wistfully eyeing driftwood-strewn Beverly Beach. On a nicer day, we would have enjoyed walking there, searching for agates.

Instead, we harbored at the Oregon Coast Aquarium (admission fee) in Newport for an up-close view of the ocean world. At the recreated Orford Reef habitat, striped tiger rockfish and halibut with two eyes on one side of their body swam by. In the outdoor pools, sea otters amused us with somersaults; in the aviary, a tufted puffin “flew” underwater.

Yaquina Head and Lighthouse on the Oregon Coast ©Laurel Kallenbach

While we were at the Aquarium, the rain stopped, so we drove to Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area (admission fee), another prime whale-watch venue on the Oregon Coast. This narrow spit extends a mile into the Pacific, and an 1873 lighthouse perches atop the basalt cliffs. Yaquina Head affords a 360-degree view, but for a really high vantage point, we climbed the 110 spiral staircase steps to the top of the lighthouse. Cormorants, oystercatchers and harbor seals were some of our sightings—but still no whales. We hiked down to Cobble Beach, where high-tide waves jangled the polished black stones, creating a pebble chorus.

That evening, Ken and I developed an appreciation for storm watching—while soaking in our oceanside hot tub. The rough surf was mesmerizing. “Ooh! Aaaah!” we exclaimed as wave after wave exploded against the rocks, flinging spray high into the air. It was like Fourth of July fireworks created in white sea foam.

Thar She Blows!

On our last day at the Oregon coast, the rain slowed to a drizzle. We decided if the whales wouldn’t come to us, we would go to them. At Dockside Charter on Depoe Bay harbor, grizzled fishermen sat around tables drinking coffee. When we explained we wanted to chase whales, they shook their heads. “Won’t see anything,” they predicted.

Captain Loren Goddard, with Dockside Charters in Depoe Bay ©Laurel Kallenbach

Luckily, Loren Goddard, a captain with a sunny disposition, agreed to take us out in his 33-foot cruiser, Affair. The water wasn’t too rough, and the fog cleared five miles offshore. Loren idled the motor, and we scoured the seas for signs of whales.

“There!” I shouted, pointing wildly at a column of spray a quarter mile away. Like a puff of smoke, the blow hung in the air for several seconds, then dispersed. “Good eye!” called Loren. A minute later, we saw another blow. “He’s heading this way,” said Loren. Closer now, the whale’s dark back crested the water again, and we noticed its knobby dorsal “knuckles,” which reminded me of a dinosaur backbone.

Gray whales spouting in the water. Photo courtesy Dockside Charters

Ken and I bounced on our seat like little kids. Minutes later we spotted a pair of blows and tail flukes, and we watched two giants head south in tandem.

“I thought the visibility would be horrid, but we’re right in the middle of whales!” cried Captain Loren.

Over the next hour we saw about a dozen gray whales—none up close or breaching (jumping above water)—but we were thrilled anyway.

The next morning, the rainclouds parted. As we drove north up the Oregon Coast on our way back to Portland, Ken and I stopped at Boiler Bay for a last Pacific overlook, sans gale-force winds. We’d come to the Oregon Coast during winter in the hope we’d catch a glimpse of migrating whales on their way south to Baja for the season. And we succeeded, despite all the inclement weather that came our way. Yet in the process, we made an unexpected discovery: that nature’s wild display of oceanic fireworks was equally satisfying as finding whales in the mist.

—Laurel Kallenbach, freelance writer and editor

Beverly Beach, seven miles south of Depoe Bay on the Oregon Coast ©Laurel Kallenbach